K Kavitha questions Modi’s silence on Adani US bribery indictment

Political opponents are arrested without evidence and put on trial for months while Mr Gautam Adani walks free despite repeated and grave allegations, she said.

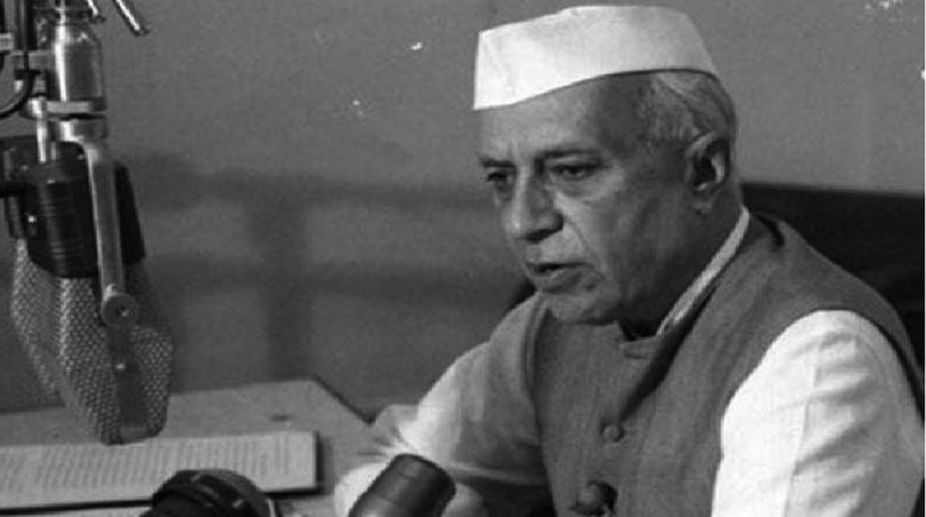

Jawaharlal Nehru (Photo: SNS)

At a time when Jawaharlal Nehru and the Nehru-Gandhi legacy are under ferocious attacks by the BJP and its leader, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, I consider it my duty as an Indian and also as someone who watched Nehru and studied him closely for over two decades, to try and repel these attacks and to present his true, quintessential personality.

Nehru was an extraordinary individual whose human qualities defied description and transcended the normal yardsticks of measurement. My old friend, Professor Govind Rajurkar, a political scientist and author of an erudite biography of Nehru (Nehru: Utopian Or A Statesman, 2014), studied and observed Nehru all his life and did his PhD on Nehru’s nationalism, told me recently of his three long meetings with Nehru as part of his research.

Each meeting, he said, revealed new facets of the man’s multi-faceted personality. Although Nehru studied botany for his graduate tripos at Trinity College, Cambridge, and later Bar-at-Law at Middle Temple, England, he was equally at home in domestic as well as international politics.

Advertisement

In the same breath he would talk about Kautaliya’s Arthashastra and John Smith’s Wealth of Nations. His knowledge of Indian and world history, he said, was phenomenal. How could he write his own world history (Glimpses of World History) sitting alone in a prison cell without access to any library or external source. And he has demonstrated his remarkable knowledge of Indian history in his most creative work, Discovery of India.

The qualities which impressed him most, Prof Rakurkar added, were Nehru’s simplicity and unobtrusiveness. Nehru would come and greet him at the door for each meeting and he would walk up to the door to see him off after the meeting.

Nehru had all the mental and intellectual paraphernalia not only to become India’s first Prime Minister but also the Prime Minister of England or the President of the USA, if he wanted to. In November 1956, I was a student when he came to inaugurate the new state of Andhra.

I went to listen to his speech. On the same day, the UK and France had jointly invaded Egypt. Nehru condemned the two countries unequivocally in his speech and wondered ‘who made them the policemen of the world?’. Some two decades later, while working in England, I read the Memoirs of Sir Anthony Eden, who was the British Prime Minister at the time of the Suez war.

He quotes Nehru’s speech in Hyderabad extensively and regrets that someone like Nehru had criticised him so strongly for the Suez attack. This shows that Nehru’s voice had reached the highest echelons of the British government.

His foreign policy, based on the principles of non-alignment and non-interference, has paid major dividend to India, and any deviation from it will not be conducive to India’s interests. Neighbouring countries, which have relied heavily on one super-power or the other, have little or no voice in international affairs.

In post-independence India the integration of hundreds of princely and other states was a Herculean task. Nehru chose the ‘Iron man of India’, Sardar Patel, as his Home minister and entrusted this gargantuan task to him.

Those who are interested in knowing more about how efficiently and expeditiously Patel integrated the states should read the classic book, The story of the integration of Indian States by V K Menon, the then Home Secretary of India.

But to claim, as Prime Minister Modi recently did in the Lok Sabha, that Patel and not Nehru should have become the first Prime Minister is neither fair nor historically accurate.

Mahatma Gandhi chose Nehru as his political successor and he became the first Prime Minister. There is no evidence to suggest that there was a competition for the job between Nehru and Patel.

Both were among the political heavy weights of the freedom era and not adversaries. I don’t think Patel would have preferred to be the first Prime Minister of India.

However, I agree with the Prime Minister that he perhaps had the personality to solve the Kashmir problem as Prime Minister much sooner.

Nehru was both a visionary and dreamer. His vision of India encompassed Indian satellites and rockets in space, an India capable of producing nuclear energy both for peaceful purposes and for developing nuclear weapons, a technologically advanced India with enough IT expertise and capacity both for the country and abroad and a nation self-sufficient in food.

Thanks to him, India has made tremendous strides in all these fields and especially IT. He started his IT project by establishing five Indian Institutes of Technology (IIT) in Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai, Kharagpur and Kanpur with foreign aid. The IITs have multiplied in the last 50 years and there are 16 IITs in the country now.

As for their quality and output, the chief of CISCO in the Silicon Valley described them ‘as equivalent to MIT’ during a visit to India. Thanks to Nehru’s vision and the IITs, India is the biggest exporter of IT engineers with more than 30,000 of them now working in the USA and occupying senior-most positions in some of the most prestigious organisations.

Not only is the CEO of the world’s biggest and most well-known IT company, Microsoft, an Indian (Satya Nadella), but also the CEOs of Google (Sunder Pichai), Adobe (Shantanu Narayan), Sun Micro (Vaid Khosla), SanDisk (Sanjay Mehrotra), Nokia (Rajiv Suri), Net App (George Kurian) and Cognizant (Francisco D’Soza). The former heads of the City Group and McKinsey were also Indians.

Whom should these CEOs be grateful to for their redounding success: Jawaharlal Nehru or someone else? His education minister, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, an eminent scholar and educationalist, introduced many radical reforms in the fields of education and science and established CSIR, the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, along with several national laboratories (physical, chemical, etc.)

It was Nehru’s imagination and unceasing efforts that resulted in the most spectacular and rapid development of water resources and irrigation in the past 70 years.

The total irrigated area in 1947, when the British left, was about 10 lakh (1 million) hectare and it is now approaching one crore (10 million) hectare. India today is not only self-sufficient in food but also a net exporter of food.

According to the Register of Dams published by the International Commission on Large Dams, some 15,000 small, medium and large dams and reservoirs have been indigenously designed and built for irrigation and power since 1947.

Nehru has described these dams as “modern temples”. It bears recall that in the 1950s and Sixties many economists in the West had predicted in their papers and essays that millions of Indians would die of starvation by the end of the century due to severe floods, famine and drought. Thanks to Nehru these predictions did not come true.

The last famine in India occurred in Bengal in the 1930s under British rule. Hence, when his name was not even mentioned at the inauguration ceremony of the Sardar Sarovar dam, the foundation of which was laid by Nehru, I was shocked as an engineer who had devoted 44 years of his life to water resources and irrigation development in India and abroad. Nehru’s role in India’s water resources development to me is as important as Leonardo di Vinci’s role in creating the Mona Lisa.

Nehru’s economic policies have also come under harsh criticism recently, although it was a Congress-led government under the then Prime Minister, the late P V Narasimha Rao, and the then finance minister, Manmohan Singh, which took the historic decision in 1990s of liberalizing the economy.

What pains me and many others most is the unfounded and irrational description of Nehru as ‘Mr 3%’. Even Gurcharan Das, a former CEO of an American multi-national company and the author of such an illuminating book, India Unbound, falls prey to the same temptation in his book.

What these critics don’t seem to realize are the externally-imposed limitations under which Nehru operated. He neither had the trained manpower nor the necessary institutional or physical infrastructure to embrace the free market economy.

He developed them through his not-so-perfect Five-Year Plans. Despite a delayed entry into the free market, India, thanks to Nehru, is the 7th economic power in the world today.

Nehru’s love for literature continued till his death in 1964. The following four lines from a poem by the American poet Robert Frost, which he scribbled in his diary before his death, tell us of his unfinished mission:

The woods are lovely dark and deep, But I have promises to keep, And miles to go before I sleep And miles to go before I sleep.

The writer, an NRI living in London, is a retired UN/ World Bank consultant. He is a freelance writer and author.

Advertisement